#

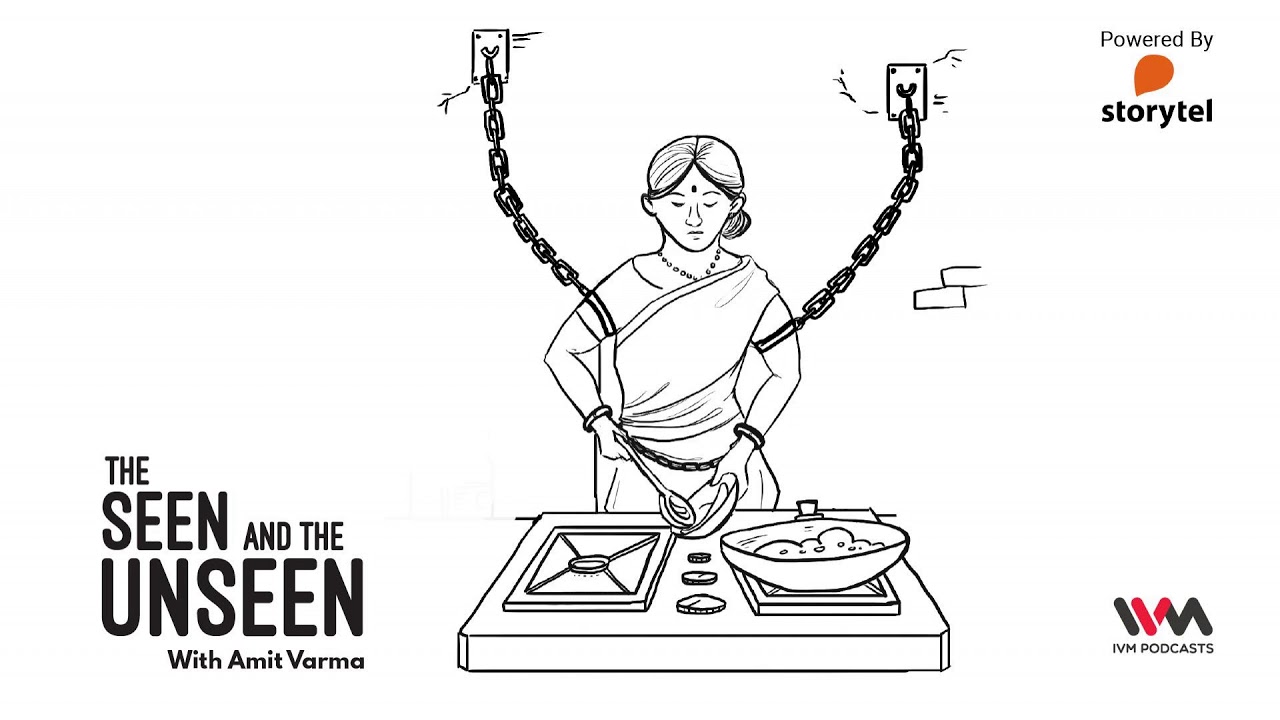

What would India have looked like if our women were as empowered as men?

#

But even economic estimates cover up the real problem.

#

Welcome to The Seen and the Unseen, our weekly podcast on economics, politics and behavioral science.

#

Please welcome your host, Amit Varma.

#

Welcome to The Seen and the Unseen. My guest on the show today is the journalist Namita Bhandare,

#

whose journalism I've been a fan of for many years and I'm so glad I finally got her on the show.

#

The subject we are going to explore today is women at work.

#

A subject on which she wrote a brilliant nine-part series on India spend a couple of years ago,

#

which will be linked from the show notes.

#

She's written perceptively on Indian society and not just women's issues for literally decades now.

#

And I'm going to make you wait around 60 seconds more as we go into a quick commercial break.

#

Namita, welcome to The Seen and the Unseen.

#

Hi Amit, thanks for having me here.

#

Namita, before we get to the rather depressing subject at hand,

#

tell me a little bit more about yourself. How did you get into journalism and so on?

#

Okay, just a small correction before we start talking about myself.

#

It's not depressing. The women of India to me represent a great hope and a great aspiration.

#

We will talk about that in detail. I will tell you a little bit about myself.

#

I'm a mother of two women, 26 and 24.

#

I have been a journalist for nearly 30 years, starting my career in a lot of publications that have since folded up,

#

including The Indian Post, Sunday Magazine, where I had some of my best experiences of long-form writing

#

and finally ending with Hindustan Times.

#

I was also Mint's first gender editor. I believe the country's first gender editor ever.

#

Sukumar took a great risk with me and I will always be grateful for that big break.

#

We had a lot of fun exploring gender, not as a little silo.

#

You know, we did talk about, I remember when we first talked about how we should be covering gender,

#

we wondered whether we should have a weekly gender page.

#

And then decided that that was just too retro, you know, because gender does not exist in a silo.

#

We are 50% of the population and gender is everywhere.

#

It means looking at your op-ed pages. Do you have enough women's voices coming in?

#

It means looking at your hardcore business pages. Are you quoting enough women?

#

And it was interesting because we actually thought about bringing in a gender editor,

#

much before The New York Times did. The New York Times now has an entire gender team.

#

I've met with some of them. They're fantastic women, but we were first.

#

That's amazing. And you know, like I started my career in the 90s, but you started in the late 80s.

#

And I remember back then, it almost felt like women are sort of stereotyped in journalism

#

and the kind of roles they occupy. Like if you, you know, women were supposed to do the soft stuff,

#

the features and so on and the hard news and the reporting wasn't something women really did.

#

Is that kind of true? And did you face any barriers back then and the kind of work you wanted to do?

#

You know, Amit, forget about media. With every generation of women,

#

there has been an entirely new set of struggles.

#

So the generation before me, and I'm talking about the great women journalists like Usha Rai

#

or Barkha's mom, you know, so these were women who were opening the doors.

#

Kumi Kapoor, they were opening the doors. You never saw women in the newsroom.

#

There were no separate toilets for women because women were not supposed to be in the newsroom.

#

So that was a different battle. They opened the doors for us. We stood on their shoulders.

#

When I came in, yes, you're right. There was the stereotyping. Women were supposed to still do the soft stories.

#

You were on the art beat. You were on the profile beat. The magazine sections were filled with women.

#

That has changed. That has changed. Today, when you walk into a newsroom,

#

you will be struck by the number of women you see on the floor.

#

And yet some things persist. So you see the women in the news floor in abundance.

#

But the people in the corner rooms in the corner offices are all men.

#

So that still has to be the very few women. Television has been great

#

and has been far more progressive than print in that sense, where you have a lot of women who are in charge.

#

NDTV is a sterling example where women have been in charge from day one.

#

Print has been a bit slow to catch up. So you see a lot of women in the newsroom, not so many women in leadership positions.

#

What was your early journalism like? How did it evolve?

#

How did your interest sort of evolve in the directions it did in?

#

And at some point, you chose to give it up and go freelance. So tell me a bit about that.

#

Yes. So I had done my masters in journalism from Stanford.

#

I came back and frankly, the masters at Stanford was a fig leaf.

#

I was lucky to get a fellowship and so I could run away.

#

But it was a fig leaf because I knew that if I stayed on in India, I would marry a bhala larka from a bhala family

#

and fulfill my mother's wildest dreams. And so I said, I mean, I had other plans.

#

So, you know, it was just, you know, we forget now because we see so many women.

#

I mean, women studying is not a big deal.

#

But when I went in 86, 87 to the US to study, there were hardly any women who were going abroad.

#

You know, it was a big deal. But because I had a fellowship, my mother could not exactly object.

#

You know, I was saying, I don't need your money. I'm going.

#

Which Indian will say no to freebies?

#

Well, this was yes, exactly. So my my mother was not happy, but she understood.

#

And then, of course, when I came back, I said, I want to come back to Bombay.

#

I started working in the Indian Post and it was exhilarating, you know, to be living alone in Bombay.

#

At that time, I'm talking about 89, 90.

#

The Indian Post was a very young paper full of just brilliant people, you know, Alan Twigg, the late film critic.

#

He was a friend of mine. I mean, there was just an energy and a buzz that Vinod Mehta brought with him to the paper.

#

It's an old story. The Indian Post folded up, actually.

#

Vinod went on to forming a new paper. I did not go at that time.

#

I was young, idealistic and foolish, and I believed I will stay on.

#

And so we were about 15 of us helped by the Bombay Union of Journalists taking out this paper somehow or the other every year, every day.

#

I'm sorry. And then it was eventually bought by Gujarat Samachar.

#

And it was basically it was, you know, we had seen the writing on the wall.

#

It was time to move on. I then ended up working for a while with Sunday magazine.

#

As I mentioned, some of my best years, I learned a lot.

#

Veer Sanghvi was the great editor and a great teacher and very trusting in allowing young people, inexperienced people to go out and do stories.

#

And in his mind, there was no, you know, gender bias in the sense that the hard political stories were being done by men.

#

In fact, our great political editor who continues to write a column for Business Standard was Aditi Fadnis, a wonderful teacher, a wonderful mentor and a wonderful role model.

#

And so we had women in charge of the hard stuff, the nuts and bolts.

#

So there was nothing that we could not do, whether it was foreign policy, whether it was politics, whether it was back of the book, the soft so-called women stuff.

#

We did it all. We were everywhere.

#

It was a small team. You were expected to do it all.

#

And then Sunday, kind of as Sunday was folding up, I moved to India today.

#

I worked there for a couple of years.

#

I then eventually went back to working with Veer in the Hindustan Times.

#

I remember 9-11 had just happened and he reached out to me.

#

He said, why don't you come back, come back and work in Hindustan Times?

#

We'll work together. Once again, very trusting in terms of the kind of leeway and the kind of responsibilities he was giving.

#

By this time, I was already a mother of two young girls.

#

And so my condition with Veer was I'll come back, but I will work part time.

#

So I need to be out of here at five o'clock.

#

And he understood that.

#

And so my pay was also part time.

#

And then I realized very quickly that part time was a convenient designation to pay me half of what everybody else was being paid.

#

But my output was actually full time because I was producing a page a day.

#

I was writing stories. I was editing stuff.

#

We had a youth page, a weekly youth page, which I was in charge of.

#

And of course, it was all the undercurrent that you got from your male colleagues.

#

Because at five o'clock, when I was picking up my bag to head home, there were guys who were saying, oh, how nice of you to drop in Mrs.

#

Bhandare. They would call me, you know, how nice of you to drop in Mrs.

#

Bhandare. Have a good time.

#

And I was like, you know, bloody hell, you just got in half an hour ago because you were at the press club and you were having like a big boozy lunch

#

and then downing a couple of black coffees to get over the big boozy lunch.

#

And you're getting down to work now.

#

I finished my work because I've been here since 10 o'clock.

#

So it was an interesting insight.

#

Of course, at that time, I didn't know I'd be doing the women and work series.

#

But I was kind of I was my first example of just how impossible it was to balance this, this work life balance.

#

You know, you're kind of trying to. And so I went full time.

#

I told you, I said, my output is that of a full time person.

#

I want my salary, you know, and I think women don't do this enough.

#

We don't ask for the money that we think we're worth.

#

And so I told I told him, I said, I think you should pay me a full time salary and I will work full time.

#

And so I started working full time, which meant because I was editing the Saturday paper at the time.

#

I would never get home before midnight on Friday night because I had to put the paper to bed.

#

And because I wanted to get a head start on Friday, I would be working late to Thursday, which was like 10 o'clock.

#

And so what was happening in a predominantly male, you know, the heads of department were all men.

#

So whether it was the designer, whether it was the photographer, whether it was the desk guys, they were men.

#

So even if you came in at nine o'clock, the other guys were not coming in till 11 o'clock, 12 o'clock.

#

Then you'd have these long edit meetings. Then everybody would run off to press club.

#

Then so your workflow began only at five o'clock.

#

And if you're heading a department, you realize that you can't work alone. You need your team with you.

#

So and here is a generational change. So I mean, I tried it for a while and then it was just untenable.

#

My children by then were adolescents.

#

I had a eureka moment, actually, literally in the in the shower where I said, you know, if I drop dead,

#

my family is not even going to get a discount on the obituary, you know, let alone a free subscription to HD for even the next six months.

#

But for my children, I'm indispensable. And it was just something had to give.

#

And so I decided to chuck up full time working. And I went into writing a column and I went into freelance work.

#

It was a struggle, but I've never looked back. I've never regretted that decision.

#

But coming back to the generational change.

#

Ten years later, when my friend Priya Ramani took over as the editor of Mint Lounge,

#

she had basically an all women team. And so she laid down the you know, so she could lay down the law.

#

And that was the difference. I could not lay down the law because I was dependent on all these male colleagues

#

who simply could not understand why they needed to come early and leave early.

#

So she laid down the law. She said everybody in at 10 o'clock and it's pens down at five o'clock.

#

Go home. And even if you're not married, it doesn't matter.

#

Even if you don't have children, it doesn't matter. Go home, watch a movie, read a book, because there is life outside the office.

#

And so that's what she she changed the work environment, at least in her department. I was unable to do that.

#

Good for Priya. And you've written a really nice piece about, you know, going freelance and all of this in a site called Shero's.

#

So that's a lovely piece. And I'll link that from the show notes.

#

How has, you know, two sort of questions.

#

One is that when you did your course in journalism in Stanford,

#

there must have been certain expectations you had of what journalism should be, what are the best practices and so on.

#

So question number one, how was the reality different when you got down to India?

#

Though, of course, you did work with good editors in terms of Vinod Mehta and Vir Sanghvi.

#

But how was the reality different? And looking at journalism in India today is 2019.

#

And when you compare it to, you know, 30 years ago when you started, what are the big changes that you've seen?

#

So at Stanford, we pretty much followed the American style of journalism, which is objectivity is king.

#

You know, you are objective, come what may.

#

You are never part of the story. And I began my journalism pretty much like that because that is what Vinod also believed.

#

And that is what we sang. We also believed you were allowed your stylistic flourishes, but you were supposed to be objective.

#

You were supposed to be speaking to all sides of the story and so on and so forth.

#

And I pretty much believed as that tenet of journalism as a gospel truth.

#

I never questioned it until December 2012, which is when Jyothi Singh Pandey was gang raped and murdered in a bus in Delhi.

#

And at that point, Amit, it became impossible for me to say I am objective.

#

It became impossible for me to say I am not part of the story because I was also protesting.

#

I'm also a citizen. I'm also a mother. And that crime and that that story just moved me in a way that I cannot adequately explain.

#

Even today, I remember the first time I met her mother, I was making a film for Channel News Asia in Singapore.

#

And we were four of us in her little house. At that time, they had a two bedroom house.

#

They've now moved to another place, which the government gave them and the mother.

#

I'll never forget that. I mean, it's one of those pivotal moments in journalism.

#

We just reach deep inside you. So the mother was the daughter had just died maybe a month ago.

#

And she was it was still winter and she was lying in bed and she just looked up.

#

She had this bright pink blanket covering her and she looked up at me.

#

And we were three or four people in the room. There was a cameraman. There was a sound recordist.

#

There was me. There was the producer. And we just wept for five minutes.

#

We sat in the room and we just cried and cried and cried.

#

And that's when I realized that I can no longer be objective.

#

So today, my question is not are you objective about the story today? My question is only are you fair?

#

So I write on gender and I feel that it is impossible to be objective about gender.

#

And it is also morally wrong. Why should I be objective about rape?

#

I mean, can you be objective about rape or crimes against women or patriarchy or caste?

#

Because, you know, you have so many intersections, caste and gender.

#

I feel it's impossible and it's morally wrong.

#

I feel it's ethically and morally I'm not going to be objective about rape.

#

And I'm not going to say, oh, am I being objective? I must present the rapist point of view.

#

No, I cannot be. But I can be fair.

#

So if you look at, for instance, this much maligned section for 98, one of the stories that I did do for Mint

#

was looking at why this 498A section, which is the dowry section, is misused by women.

#

So fair. I'm balancing it out. Right. I'm not saying that I'm giving up.

#

I'm not saying dowry death is great or dowry is great because I cannot take that position.

#

And no citizen of a modern democracy can take that position.

#

You know, I believe in the Constitution. I believe in equality.

#

But I can say, well, why is it being misused? Where are we going wrong?

#

Is there something we can do to rectify it?

#

You know, I think at some level, objectivity in journalism can be overstated

#

because much as one should attempt to be objective and see all sides of the issue,

#

it's also true that all human beings are fundamentally biased anyway.

#

And just the data you choose to present in your story, the way you choose to present it kind of affects that.

#

And I must say that having read so much of your reportage on, for example,

#

the state of women across the country and in Haryana, which we'll talk about later,

#

I don't really sense anything that is not objective there.

#

I mean, you just present the data and let it speak for itself.

#

Yeah. Well, that's some of my, I mean, some of my journalism in one of my journalistic hats.

#

I'm a columnist, so I'm expected to present a point of view and a perspective.

#

That is the very definition of my job.

#

People read the edit page because they want to know, what do you think? Right.

#

And then there is the data journalism, which I do for websites like India Spend

#

or for even other websites where you're asking, OK, have I spoken to all sides of the story?

#

Am I presenting? And you're absolutely right.

#

You look at data because if you look at a bare report, how you interpret that report is really up to you.

#

What am I looking for in that report?

#

So for a lot of my gender reporting, I am looking and I'm saying, well, this is according to government,

#

because when I'm challenged sometimes on social media, for instance, domestic violence,

#

the figure that seems to shock everybody as if it's something that is happening on planet Mars

#

is that one in three women have experienced or are experiencing domestic violence at the hands of a spouse.

#

And they say, no, no, it cannot be. How can it be?

#

That means one in three, if I'm sitting in a let's say in a bus where there are ten women,

#

I mean, you know, you've got I'm very bad with math, but you know what I mean.

#

So you have, you know, one in three who have experience.

#

I mean, absolutely. So the data doesn't tell you that story.

#

And then you tell. So you say, well, and so people say it can't be happening.

#

And you say, well, no, it happens. This is National Family Health Survey for.

#

And this is the data on page. So and so this there's the link.

#

And please go and look at it. And then you say, oh, you know, but it must be happening to those people.

#

It doesn't happen amongst us. You know, it's like 30 percent.

#

It doesn't happen amongst us. Well, you know, where do you think it's happening then?

#

And what I'm struck by is, you know, when all of this difficult data comes up and all these numbers come up,

#

which indicate that, you know, women are having the kind of time they're having that men get so defensive.

#

Of course. And there is much to be defensive about, you know.

#

And there's always my favorite accusation that comes from men is that, oh, you are women of privilege.

#

You know, the I was at the Brookings Institute.

#

We were having a very interesting discussion on gender in the northeast with Patricia Mukim,

#

who is the editor of Shillong Times. And Manishankar Iyer got up and he said,

#

I think y'all are all because we were talking about 33 percent reservation

#

and the need to get more women in parliament. And he said, but y'all are all Parkati Aurats, you know.

#

I mean, he used Parkati in inverted commas, of course.

#

And I'm like, yeah, you could be a woman of privilege and still be discriminated against.

#

So maybe I am not as discriminated against a Dalit woman who's living in a village

#

or a tribal woman who's having her land being stolen or, you know, being shot by the land mafia.

#

But I am being discriminated against. There is no denial of that.

#

And I think men simply do not see they are oblivious to the lived realities of women.

#

They just have no idea what it is like to walk on the street and have everybody stare.

#

They have no idea of what it is like to walk in the street and never make eye contact.

#

That's the first rule. You learn it as a child.

#

You do not make eye contact because the other guy is going to either be making a lewd face at you

#

or blowing you a kiss or scratching himself somewhere.

#

So you just walk straight. It's like you just have these blinkers.

#

You're like a racehorse. You're just walking straight and you're not looking anywhere.

#

You've got your arms crossed around so that nobody touches you in parts that are vulnerable.

#

Men don't get this. They don't.

#

And so, you know, the best men will tell me, I didn't realize. I'm sorry. I didn't realize.

#

In fact, as we were, you know, chatting about before we met,

#

I mean, that's one of the realizations that happened to me well into my adulthood in the last few years,

#

is that, you know, in everything I do, I don't need to, my gender is not a factor.

#

I could be walking in the street. I could be meeting someone new at a party.

#

My gender is simply not a factor. I can make eye contact with anyone I want.

#

I can smile whenever I want. I don't.

#

But in every single thing women do, including Prakriti women and women of privilege,

#

your gender does become a factor. It's hanging over you like a shroud.

#

And you have to just be careful all the time.

#

And this extra layer of consideration that women have to carry about in their everyday lives is almost heartbreaking.

#

And I would not say that men are culpable for this,

#

but it is certainly incumbent upon them to kind of take this into consideration.

#

Absolutely. Men as well as women.

#

But before I get to that, I just wanted to share an interesting story,

#

which goes back again to the December 2012 protests.

#

So I'm walking up Rajpath towards Rashtrapati Bhavan, which is where the crowd is moving.

#

And I'm walking with a male friend of mine.

#

We're walking together and there is this very striking woman.

#

I never saw her face, which is tall woman walking.

#

There's a yellow line, a thick yellow line that divides the two sides of the road, right?

#

So she's walking alone, bang on the yellow line.

#

And I tell my friend Javed, who I'm walking with, I said, Javed, there are four men coming on the opposite side.

#

I can see the men coming on the opposite side towards this woman.

#

OK. And I tell my friend Javed, I said, Javed, just wait and watch what will happen.

#

And here we are at a protest for women protesting violence against women.

#

And these are four men. They're inoffensive, harmless guys.

#

They're having fun. They're slapping each other on the back.

#

They're laughing. They're walking in the opposite direction.

#

Sure enough, as soon as they come close to the woman, the woman gets off the yellow line and walks around the men.

#

The men are not doing anything.

#

But there is some inbuilt signal in this woman that tells her get off the line because these guys won't budge.

#

And this is this is what we learn from childhood, whether it is in a public park,

#

whether it is traveling in the bus, sitting next to a guy who is nicely spread out.

#

I was on a flight very recently and this man, you know, I'm on the middle seat.

#

So the two men on each sides have taken the armrest because, you know, it belongs to them.

#

So, you know, we are this is our conditioning.

#

We are taught from a very young age, public spaces belong to men.

#

You do not belong here.

#

In fact, on flights, I myself seen that even if you don't take the armrest and there's a woman next to you,

#

she will not put her elbows there at all.

#

Just completely avoid the situation.

#

While if it's men, you're basically just elbowing each other by the end of it because male ego won that space.

#

Which woman wants to get into that elbow fight?

#

You just sit hunched, you know, with your arms.

#

I actually encourage my listeners, both men and women, to actually do this.

#

Let's sit for a while in a public space like a cafe or looking out into a park

#

and just see how people walk around and the way they behave.

#

And it's visible every day in front of us and yet invisible, which is kind of poignant.

#

Yeah. So when you're talking about the unseen nation, I found your introduction, by the way, very beautiful and very poignant.

#

And if you go, I'm not talking about going to a small city or a small town.

#

I'm saying step outside in Delhi.

#

You're right outside here. There's a park.

#

I promise you, I guarantee to you, all the kids who are playing sport,

#

whether it's cricket or ghillie danda or whatever, are boys.

#

If you do see girls in the park, you'll either see very young children who are on the swings and slides

#

or the adolescent girls are just walking.

#

They just keep going for seh.

#

They're just walking round and round.

#

It's like girls do not have a right even to play.

#

We are recording this in house cars, by the way, but this is probably true of pretty much every park, frankly.

#

Let's kind of move on to the subject of today's episode.

#

And, you know, I'll kind of question what you said earlier a little bit in the sense that I think a lot of the data

#

that you've presented in your India, spend pieces, some of which I'll be quoting back at you, is objective.

#

I mean, the data speaks for itself.

#

It doesn't matter who you, the writer, are.

#

The data does a whole job and there's no other way of looking at it.

#

You know, much as people like I often think that in India, every crisis we talk about has a deeper crisis

#

embedded within it, which is a women's crisis.

#

For example, people talk about the crisis in agriculture, which I have written about at length as well.

#

And within that, there is a greater crisis because women have it far worse.

#

And one of those crisis, which, you know, again, I've had episodes on the jobs crisis in the past.

#

And within the jobs crisis, there's a deeper crisis and that has to do with women.

#

And I'll quote the most interesting statistic of your series, which, you know, I found in the first piece

#

that you wrote in the series on India Spend.

#

Quote, in the first four months of 2017, a nugget of information went by unnoticed.

#

While jobs for men increased by 0.9 million, 2.4 million women fell off the employment map, according to the CMA.

#

If the number of women who quit jobs in India between 2004-05 and 2011-12, the last year for which census data is available,

#

was a city, it would be 19.6 million, the third most populated city in the world after Shanghai and Beijing.

#

And this, you know, the first time I came across this, and of course, since then I've come across this repeatedly,

#

including in your pieces where you've analysed it so well.

#

And it just blew my mind that I'd imagined that we've liberalised, we are progressing, there's globalisation, there's technology.

#

More women should be working and yet less women are working. Why is that?

#

That is absolutely true. And again, the unseen crisis, the unseen nation that you spoke about.

#

You know, we in media, we celebrate the exceptional.

#

So the first woman firefighter, everybody is writing about her and she's getting awards and she's everywhere.

#

She's on TV, she's being interviewed.

#

The 19.6 million women who lost jobs in just that decade is that trend has not fallen.

#

When I started doing the series, I was quoting 2011 census figures and I was quoting the 2017 World Bank report

#

where women's labour force participation in India was 27%.

#

When I finished the series and there are 12 articles, not 9, sorry for that little correction.

#

I'm so sorry, I just followed all the links from each of them.

#

Yes, I think they got tired of putting up the links because, you know, it was the same.

#

So anyway, when I finished the series a year later, the economic survey of 2018 had put women's labour force participation at just 24%.

#

In a city like Delhi, what is the labour force participation? Take a guess. Roughly.

#

15%. This is the capital city of India.

#

And it is a mystery as to why this labour force, why are women falling off the labour map at a time of rising education?

#

And you know, of course, the great success stories of India is that women, girls now enroll into school, primary, secondary, as well as high school, at the same rate as men, as boys.

#

There is no gender, we have bridged that gender gap.

#

That is actually one of our great victories.

#

Again, an unseen nation.

#

I don't know why the government has not gone to town talking about it because it is rightfully a grand achievement.

#

This is primary and secondary education.

#

Yes, there's a tiny gap.

#

I mean, the last year's figures, I think there's a tiny gap of about 1 point something percent in high school.

#

But primary and secondary, there is no gender gap at all.

#

It's a remarkable achievement for any government where the gender gap has been so huge in education.

#

So girls are in school, you know, for a variety of reasons.

#

Governments are giving them cycles.

#

There's the midday meal.

#

I mean, these are all great game changers and the girls are in school.

#

Let's not talk about quality of education because it's the same quality of education for girls and boys.

#

Fertility rate is declining.

#

So why are girls dropping out of the workforce?

#

I mean, it's a huge mystery.

#

And why aren't we talking about it?

#

It's one of those silent crises which nobody wants to talk about, not governments and not even women themselves.

#

In fact, this is another startling statistic which refers to justice from one of your pieces.

#

A quote, in rural India, 67% of girls who are graduates do not work. In towns and cities, 68.3% of women who graduate don't have paid jobs.

#

So the good news, of course, is that one reason why women are dropping out of the labor force is because they are in school.

#

And I have been to a university in a rural area in Haryana where girls from villages are even doing their PhD.

#

But education has become an end in itself.

#

You know, parents today are willing to say, haa beta padlo, padho, padho, padho.

#

But after padhai, then what?

#

After you do your MA, you do your PhD.

#

At what point do you start working?

#

That message is not coming through.

#

So nobody is really saying, no, you have to go out.

#

You have to get careers.

#

We're not still telling our or we might even be telling our daughters, you can have a job.

#

But we're still not talking about having a career, a career as being defined as a job that you do for your whole life,

#

you know, where you progress, where you go.

#

So boys are being conditioned that, no, you've got to work.

#

And this is the destiny of your life for the rest of your adult life.

#

Right. Girls are not being taught that we are still telling girls your priority is your family.

#

Your priority is your husband, your children, your in-laws, the parents, the everything job you can do.

#

This is your natural job.

#

This is what you were born to do.

#

And this is again a finding I'm kind of baffled by because not that they don't want their daughters to work.

#

That's been an age old story.

#

But the fact that they then get asking them to study at all.

#

I mean, because earlier, you know, there was this conception that back in the day that you don't educate a girl too much because she'll talk back to her husband and all of that.

#

And now if they're encouraging them to study, get a PhD, but don't work after that.

#

And I don't get that. Is it kind of to keep them out of troubles way?

#

So they are, I mean, I don't understand.

#

It's to use our favorite Indian expression, no time pass.

#

If she gets married, okay, study.

#

You don't want her to work.

#

You don't want her to get into the job force because that may be something that goes against her marriage.

#

I'm not saying everybody's doing PhD.

#

I mean, we're talking about a very small percentage.

#

But there is no stigma anymore in education.

#

You know, so nobody is saying that.

#

I mean, it is accepted that your daughter will now do at least up to class 12.

#

But after that, what happens?

#

Why are we not telling them or why are parents not saying, well, you need to work.

#

And this is as important as having children and marriage and everything else.

#

So, in fact, Farzana Afridi, the economist, she says, you know, people talk about economics.

#

Talk about the motherhood penalty.

#

And this happens globally, right?

#

You become a mom and you fall off the workforce.

#

But Farzana Afridi talks about the marriage penalty.

#

She says the first stumbling block is actually marriage.

#

So there is a tiny window where women might work.

#

And that tiny window is between studies and marriage.

#

Workforce participation just declines.

#

If you look at workforce participation of married women vis-a-vis single women and single women, meaning before they're married.

#

If they were to become widowed, they would.

#

The workforce participation rate then shoots up.

#

Single women actually do work.

#

But single women are after marriage.

#

So if they're either divorced, abandoned or widowed, they will.

#

They are expected to work.

#

Because then I guess also they don't have a choice.

#

It's almost like the spirit of Bombay that I mean, you have to do it.

#

So even farmer wives, for instance, the farmers who commit suicide, their wives are not.

#

Very often they go back home.

#

Very often I have seen this myself.

#

They are not even given a place inside the house.

#

They build a hut in the middle of the field.

#

And they are put into Dehari or whatever it is that they can do.

#

Then they are told very clearly that we cannot afford to sit and feed you and your children.

#

You are expected to work.

#

So they become a resource of a different sort.

#

Before, while they are married, they are looked at as resources who will look after their husband and look after the house and all that.

#

But when the husband isn't there and that function is redundant, hey, you're still a resource.

#

You've got to do something.

#

You address a question in one of your pieces, which I'll kind of quote at you and let you elaborate on that, which is, quote,

#

The 2011 National Sample Survey found that over a third of women in urban India and half in rural areas who engage mainly in housework want a paying job.

#

So if women want jobs, why are they quitting?

#

What's holding them back?

#

So what's holding them back?

#

My very simple answer, if an unpopular answer, is family.

#

The structure of family is such that it imposes a tremendous burden on girls and on expectation from girls.

#

You know, where does this come from?

#

This idea that girls must grow up to look after their husbands and cook the food and and all of that.

#

Where does this idea come from?

#

It comes from the family.

#

It's not coming from some external force.

#

And it is true to a large extent of everywhere in the world.

#

When we talk about the burden of care work, it falls disproportionately on women.

#

And there is not a single country in the world, not even the Scandinavian utopian societies, where the work is 50-50.

#

There is an imbalance all over.

#

Of course, in India, that imbalance is particularly bad.

#

And depending on where women are living, they could be spending as much as five hours a day on care work.

#

It is the cooking, cleaning, caring for children and the elderly.

#

It involves the fetching of firewood, the fetching of water.

#

Women spend hours just fetching water.

#

So in fact, when people say women don't work, I take great exception to that statement because women actually work.

#

And if you were to factor in the work that is unpaid, the care work, then women probably work far more than men.

#

In fact, the figure in one of, again, I'm getting this from one of your pieces, is that unpaid work, women in India do unpaid work for five hours or 351.9 minutes a day.

#

And men do it for 51.8 minutes a day.

#

What do men do for 51 minutes?

#

So when I ask women, and I've asked a lot of women, including in places like Bombay, I say, well, does your husband help or does your son help?

#

And then they say, yeah, of course they help.

#

And I'm like, what do they do?

#

So they said, oh, when I'm cooking, he plays with the children.

#

That's unpaid work, according to the women.

#

And you get the most astounding responses.

#

So there was this one woman I remember in Bombay, and I said, tell me your day.

#

So she started telling me, she wakes up at 5 a.m., there's water, you have to stand in line, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.

#

Then she makes the lunch.

#

Then she makes the dinner.

#

I said, why can't you cook lunch and dinner at the same time?

#

Just cook it once a day.

#

She said, my husband's not going to eat basi khana.

#

My children are not going to eat basi khana.

#

So she's cooking twice a day unquestioningly, you know, because the food must be made twice a day.

#

So yeah, when the men work, the unpaid work, what does your son do?

#

I asked, does he help you?

#

If I need something, he runs to the market and gets it.

#

So that's included in the care work.

#

So regardless of what they do, it is pretty steep.

#

It's one of the worst in the world.

#

And at some level, the man in this case, the husband who doesn't want basi food is perhaps completely oblivious to what he's putting his wife through by making her cook twice a day.

#

But it's a woman who doesn't want to give him basi food also.

#

So this is the point that you were making about men and women.

#

I mean, women are a part of the patriarchy as well.

#

And there are feminist men.

#

So when you talk about the fight, the gender fight, the fight for gender equality, let's not forget.

#

Let's not forget Jyoti Singh Pandey's father.

#

We're coming back to Jyoti Singh Pandey.

#

He sold his ancestral land in his village because he wanted to educate his daughter.

#

She wanted to be a physiotherapist and he had two sons, two younger sons after her.

#

He never once said, I need money for your dowry.

#

He never once said, I need money for your brother's education because they are going to rightfully look after me in my old age.

#

She said, I want to be a physiotherapist. He sold the land to finance her education.

#

So our greatest allies can also be men.

#

So patriarchy is about gender, but it need not always be gendered.

#

You have feminist men and you have patriarchal women.

#

And another sort of point you made about why more women don't work is agency, where again to quote from your quote,

#

the 2011 Human Development Survey finds that a sizable number of women need to take permission from a family member to even go to the market or health care, said Rohini Pandey of Harvard Kennedy School.

#

And again, you quote her, in the end, it's pretty difficult to look for a job if you can't leave the house alone, stop quote.

#

And like you said, women are part of this.

#

It's even it's a girl's mother who will tell her that, no, you can't go alone or the mother in law.

#

Yeah, somebody needs to go with you sometimes.

#

In fact, in Bihar, I met women and sometimes, you know, they are accompanied to the market with some small boy, a five year old boy.

#

You know, they're holding that little boy, but that boy must go with them to the market because they cannot go alone.

#

And another sort of thing that comes in the way of women working is the sort of disincentives for employers to employ women.

#

Like, again, a quote from one of your pieces, Medha Unyal, program director of the Pratham Institute, was more blunt.

#

And here you quote the lady.

#

When you have women on the payroll, you are legally required to provide facilities like a creche.

#

So a lot of employers have a clear mandate of not hiring women.

#

Stop quote. And these sort of disincentives even come through, say, well-intentioned policies like maternity leave,

#

mandated maternity leave and all where sort of these disincentives as such exist.

#

What's your what's your feeling?

#

Let me tell you what my problem with paternity leave is when the government, the previous government increased maternity leave.

#

Of course, everybody cheered. Listen, six months. Why not?

#

You know, it's great. But when you mandate six months for women and nothing for men, I mean, in the private sector, there are some enlightened,

#

quote unquote, enlightened companies that will give you 10 days off.

#

What what is what is your messaging? Your messaging is that this is your job.

#

The man's job is nothing. So who's again you're reinforcing the stereotype of what is women's work?

#

See, what is my objection to unpaid care work?

#

My objection to unpaid care work is that when you're spending five hours a day fetching water or fetching firewood, where is the time to go into paid work?

#

So you are working. You're just not getting paid for it.

#

Right. When you bring in a mandate, when you increase maternity leave by six months, what happens?

#

Small and medium enterprises tell themselves there is a certain demographic that I will not hire a young,

#

about to be married, marriageable age or recently married woman with no children.

#

I can't afford to hire her because I can't afford to give her six months leave.

#

Right. You have to understand. So is the government subsidizing a part of that leave?

#

I'd like to know that. And my point is, why do we not?

#

We have a model in the Scandinavian countries where you have where it's called parental leave.

#

So it's three months for moms, three months for dads, and then the remaining three months you choose which one.

#

And the three months for dads cannot be transferred to the moms.

#

And I was shocked. I was on a TV debate talking about this.

#

This my objection to maternity leave and Naina Lalkidwai was on the panel with me.

#

And so, you know, if you give men paternity leave, they will all go off to play golf.

#

And I found that patronizing to the extreme because you're basically saying that men are shits and they will do nothing.

#

You give them a chance.

#

And if you mandate it and say this leave cannot be transferred to women,

#

then maybe they won't. So what happens when women get this?

#

Let's remember, we're talking about the formal sector that only hires, what, four percent women.

#

The informal sector, we're not even talking about where the vast majority of women work.

#

So in the formal sector as well, when a woman takes six months leave, let's say she's in a big company like an IBM.

#

Right. And she sees when she comes back, she suddenly finds that she's redundant.

#

She suddenly finds that I know this from personal experience talking to young women in the IT sector.

#

They say, oh, you know, when we came back from work from maternity leave six months, which is allowed to us.

#

And we came back and we said, our bosses say, don't do this.

#

This assignment is really a tough assignment. So the women.

#

So this is another interesting statistic. Right. NASSCOM did a survey at entry level.

#

Women in tech are 51 percent. Wow. But overall, it's only 36 percent.

#

And at the senior leadership level, it dwindles to single percentages.

#

The same newsroom example I gave you about women are there all across the newsroom.

#

But in the corner offices, they're only men.

#

So what happens at middle management level is that that is when your kids, you start having children or the parents grow older or the in-laws.

#

You know, there's an in-law who suddenly incapacitated has to be taken to the hospital.

#

That burden falls on women and not on men.

#

So when a woman often comes back from maternity leave, her boss will tell her, you know, very nice, lovely man, the supervisor.

#

And he's saying, no, don't do this assignment. It's a tough assignment. The long hours.

#

So the women lose out on opportunities. They lose out on the foreign assignments of the challenging assignments, because within the office, there is a culture that says you can't do it.

#

And I should at this point say that, you know, two of the editors I work with as a columnist are both women.

#

So there are some women in the corner office.

#

But journalism is very much the exception in that in that sense that I think the rate of women in journalism must be way higher.

#

Yes. And then other professions like journalism, entertainment, you know, so you do have a higher proportion of women.

#

And yes, as the generations proceed, as we started talking about how every generation had its own battles.

#

So today's battle is going to shift to the corner rooms.

#

The battle is not in some sectors and amongst a certain demographic.

#

The battle is retaining talent. So in fifty one percent women are joining tech.

#

So they're coming into the workforce, but somewhere, somewhere they just fall off because there is a glass ceiling that remains intact.

#

And I've spoken to so many women as well as men, more women than men, of course.

#

When you look about workplace design, you have to ask yourself who designed the workplace.

#

It's not designed by women. It's designed by men.

#

Men are very happy. Men have only one job. They have to go to work and they have to be brilliant.

#

That is it. They don't have to worry about who's putting the kids to bed or who's taking mom to the hospital for her checkup or anything.

#

They don't have to worry. They just get into work. Someone is looking after them.

#

And in fact, in Lean In, Sheryl Sandberg talks about the fact that every successful CEO has a wife who's propping him up.

#

Every successful woman CEO does not necessarily have that husband who's doing the same job.

#

I mean, how many husbands do we have who will say they'll give up their careers and they'll tell their wives, go out and be brilliant.

#

I'll take care of the house or I'll at least share an equal share of this burden.

#

They're very few. And when men do it, they are heroes.

#

You say, wow, look at this guy. What a super dad.

#

When a mom quits her job, she's just another mom. You know, it's no big deal.

#

No. And in fact, you know, you mentioned workplace design.

#

I'd written an editorial at around the time Me Too happened.

#

And it's interesting that if you consider the air conditioning in offices, air conditioning was essentially,

#

it was regularized in offices in the 50s and 60s when offices were mostly full of men and the optimum temperature then was fixed at whatever it was.

#

Now, since then, we've discovered that men tend to be comfortable at a particular temperature and women need a slightly higher temperature to be comfortable.

#

So in the normal office designed for a man, if the man is comfortable, the woman will inevitably be cold.

#

And this is something modern offices have simply not taken into account.

#

Well, I wish the problem was just air conditioning, but it's not.

#

But I'm talking about workplace design. I'm talking.

#

Look, women are capable of working very hard on construction sites.

#

You'll see that women can carry head loads of up to 60 kilos, but women want to work very differently from men.

#

Women need breaks. A lot of women say I need to be home at lunchtime because I need to cook.

#

There's an invalid parent or my children are coming home from school and I need to get food on the table.

#

I can come back. You know, that's why women, I mean, for me, freelancing was liberating because I did not have to spend time commuting.

#

I did not have to spend time in, you know, frankly, pretty useless meetings.

#

It freed me up and I was able to work. So I could work early in the morning.

#

I could work late at night when my kids have got my kids are grown up now.

#

But when they were younger, you put the kids to bed, you work, you know.

#

So women can work very hard and are very dedicated and have a certain discipline.

#

And then, of course, you have workplaces designed by men designing things like off sites.

#

My God, I mean, women, I can tell you hate off sites.

#

They hate off sites because it takes them away.

#

It means you're then it's a logistics nightmare because you have to plan food.

#

You have to put food in the freezer.

#

You have to see, make sure who's going to take the kids to school, blah, blah, blah.

#

Or let's take another example, networking after drinks.

#

How many women really have the freedom to do that?

#

So it's very well for Sheryl Sandberg and others to say, lean in.

#

How much are you going to lean in?

#

You can lean and lean and lean with all your might.

#

But ultimately, workplaces also need to recognize that if they are to retain female talent, then they need to do they need to lean into.

#

And in fact, the point you made about, you know, networking after work hours and all and just thinking aloud,

#

it strikes me as another reason of many, many reasons that women don't reach the corner office

#

because rising in corporate life requires so much networking and schmoozing and all of that.

#

And, you know, women spend less time networking perhaps and more focused on their jobs.

#

And they will, of course, be very wary of schmoozing.

#

So all of all of these.

#

You're taking me back to the days when I wanted to pick up my bag at five o'clock.

#

I was willing to make the sacrifice.

#

I was taking the pain of earning half of what everybody else was earning, even though I was doing as much work.

#

And but I need to be home.

#

That was a non-negotiable for me.

#

Now, if you tell me that, well, you have to go out, you have to meet contacts, you have to meet sources, you have to have drinks,

#

you have to go for off sites, you have to do all these bonding exercises so that you can bond as a team.

#

We'll take a quick commercial break now.

#

And after we return, we'll talk about your favorite state, Haryana.

#

Welcome to another great week on the IBM Podcast Network.

#

You know, the greatest place on earth to work on.

#

If you're interested in working with us, please do send us your resume.

#

Our careers are in this box dot com.

#

We're looking for people in business roles.

#

We're looking for people in creative roles.

#

We're looking for audio engineers, graphic designers, all kinds of things.

#

Also wanted to ask everybody, please tell a friend about your favorite podcast on the IBM network.

#

We really do depend on your word of mouth.

#

You are our biggest ambassadors and we'd really, really appreciate all of your support.

#

Also, if you are enjoying what you listen to, take a screenshot, tag us on social media, and we will repost that.

#

This week on Cyrus' Edge, Cyrus is joined by Eva Budd.

#

She's the head of Bollywood content at Ninex Media.

#

Eva recounts some of her favorite and not so favorite experiences interviewing Bollywood celebs.

#

Her new podcast, Ninex M Soundcast, available on the IBM Podcast Network and displays her singing talent.

#

This week, we're launching a new podcast called Football Shootball.

#

It's hosted by three diehard football fans, Gaurav Sapre, Sivaram Parmeswaran, and Karthik Iyer.

#

Tune in to get your weekly football fix that brings in-depth analysis along with unhinged banter.

#

First episode releases on Wednesday, 7th of August.

#

On the season finale of Not Just Dhan Sakh, Bobby Bright-Przin Patel meets Chef Baba Farhad Khurkarian.

#

Also the co-host of Keeping It Queer.

#

They talk about the varieties of dhansakhs and how there's no one way of cooking it.

#

On Simplify, Chuck and Naren are joined by guest Tony Sebastian for part two of the history of the Cricket World Cup.

#

On Mr. and Mrs. Binge Watch, Janice and Anirudh talk about the critically acclaimed Emmy nominated show, When They See Us.

#

On The Origin of Things, Chuck narrates a story about the early internet, smut, and an unlikely investment.

#

On Whatta Player, Mikhail Admeda is joined by comedian Joel D'Souza to discuss cricket, football, Formula One, and, of course, darts.

#

On the Habit Coach podcast, Ashton Doctor talks about journaling and narrates examples of prominent people who maintain journals of their lives.

#

He also explains how to keep a journal and learn more about your mind.

#

On The Empowering Series, Zarina Poonawalla is joined by the Managing Director of Genetic Call Net Consultancy, Vishal Keswani.

#

They talk about how you can discover a suitable career and how to deal with conflicts in any industry.

#

And with that, let's get you on with your show.

#

Welcome back to The Scene in the Unseen. I'm chatting with Namita Bhandare about women at work or, in general, the state of women in India today.

#

One of the things that fascinated me about your many pieces, both your series on India Spend and then you've written separate pieces in Hindustan Times about it over the years,

#

is sort of looking at Haryana as a case study in particular.

#

And again, I'll quote some figures from your pieces.

#

You point out that Haryana has, famously, a very low sex ratio, 836 girls for every 1,000 boys at birth among children born in the last five years.

#

This was in a data in 2015-16 and the national average at this time was 919, which itself is abysmal.

#

I mean, just as we talk about, say, an invisible country, you can also talk about a lost country of the missing women, as the famous phrase goes.

#

And to quote from one of your pieces, quote,

#

In 2015, for instance, Haryana reported the country's largest number of gang rapes, 1.6 for every 1 lakh women, according to National Crime Records Bureau data.

#

It had the second highest rate of dowry deaths at 1.9 per lakh population and the third highest rate in stalking women at 2.7 cases per lakh population.

#

And you've spent a lot of time in Haryana. Tell us about some of the sort of insights you've got about what's going on there.

#

You know, when you think about dystopian horror stories, it's almost like a Black Mirror episode, right?

#

What happens in villages that kill off its daughters?

#

You have women being trafficked from the Northeast and from other states, poorer states, into Haryana. Haryana is a rich state.

#

So it does poorly on gender indices, but is otherwise a prosperous state with agriculture and so on.

#

And so they can afford to buy.

#

So I have met women who are being imported in, being trafficked really for marriage, sometimes being shared between two brothers,

#

really functioning as sex slaves in a state that has chosen to kill off its daughters.

#

And this is not something, I mean, you're seeing this horror spread.

#

I mean, Beti Bachao began in Haryana. It was launched, if you remember, by Narendra Modi from Haryana for a reason.

#

And that was to, you know, the acceptability of daughters.

#

Recently, you must have read in the news, Uttarakhand, 130 villages that have not seen the birth of a girl for the last few months, right?

#

You know, it is, Amartya Sen wrote about the missing women. I mean, missing girls. You're seeing this happen.

#

This is not an academic or a theoretical discussion. You are seeing it happen.

#

What happens when a state does not value its girls?

#

So when a state does not value its girls, you will have a very high incidence of crime because who's going to speak up?

#

Who is speaking up for the rights of these women?

#

I mean, you've you've killed off the women, right? So you have very high crime rate. You have otherwise very poor gender indices.

#

But it is like all of India. Haryana is also filled with contradictions.

#

So one of the things that you will find in Haryana, a lot of our sportswomen, our athletes are coming from Haryana, from this state where goongat is like an accepted norm.

#

And I remember there was a big furor because one of the state magazines issued by the state government.

#

I mean, the headline was goongat ki something anban, humari desh ki shaan.

#

You know, goongat was desh ki shaan.

#

And I have been to panchayat elections where women are campaigning in goongat.

#

And you can't tell who's the candidate because they're all looking the same, because they've all covered their faces up to their knees.

#

Like goongat is literally down to their knees. And yet you have this, the Fogart sisters, I mean, rough contact sport like wrestling.

#

You know, and I think part of it comes from the fact that the desire for a government job.

#

So parents feel that this is their ticket.

#

So you will allow your daughter to play this sport in the hope that she'll get a sports quota and get a government job.

#

And the government job, as you've pointed out, is considered more respectable for them than a private job.

#

Absolutely. Private sector jobs in Haryana are absolutely looked down upon.

#

And the Jindals have set up a steel factory and I had gone and visited there.

#

And there were a few women working and right on the factory floor, you know, so this was very revolutionary for Haryana.

#

Most of them were actually unmarried.

#

So they were in that little window that I mentioned between education and marriage.

#

And one or two were engaged to be married.

#

And, you know, they were very clear that shadi ke baad, it depends on what our husband says.

#

And we know what he will say. I'm doing this for pocket money.

#

You know, that was the excuse.

#

I actually have another theory about how this whole thing of women in sport kicked off in Haryana.

#

I'd done a feature story on Sakshi Malik a few years ago after the Olympics.

#

And the trend of women entering wrestling really began in about 1997 when there was this legendary coach called Chandgiram.

#

And Chandgiram was a famous wrestler himself and he didn't have sons.

#

And in 1997, the Olympic Committee announced that from 2004, there would be women's wrestling in the Olympics for the first time.

#

And he saw that as an opportunity to get an Olympic medal for his family.

#

And therefore trained his daughter, Sonika Kalikaraman, who became an accomplished wrestler herself.

#

And Mahavir Fogat from there, who was one of Chandgiram's assistants, if I remember, trained his daughters.

#

So even the root of that, which seems like empowerment so many women in sport, even the root of that is male ego.

#

Yeah, but if the result is that women are coming forward, I wouldn't quibble about that.

#

I'm happy with male ego and thank God that there were no portable ultrasound machines as there are now going literally into technology is being used.

#

So, you know, maybe there would have been sons if these ultrasound portable ultrasound machines were going into every village at the time.

#

But because there were no sons, these girls were allowed to come up.

#

Yes, I get your point about it being a double edged sword, but look at it from the other side.

#

At least they came up. At least girls today have role models.

#

I mean, another point you made in your series was about how when a woman works, it is not only that that one woman has a job and she's working.

#

It has a huge number of knock on effects around her.

#

Tell me a bit about that. Most of all, on her own standing, on her own self esteem, on a whole sense of who she is within the family.

#

She suddenly gets a certain enhanced status because she's bringing in money.

#

She's bringing in prestige. She definitely gets a say in household decisions.

#

She's a person. She's not just the roti provider or the child nurturer.

#

You know, she is a person with a job and an identity.

#

So I think that is something that is very, very important when women work.

#

Let's forget about GDP and what it does to the economy.

#

And of course, she becomes a role model for her daughters, the daughters of an employed mom.

#

I'm more likely to be employed themselves, you know, because they accept that as normal.

#

The sons see their moms going out to work.

#

And so they say, well, you know, it's OK if our wives do the same.

#

So it is a virtuous cycle.

#

I don't see a downside to it at all, except, of course, a downside to the woman's own sense of stress and managing the hundred things that she must multitask in order to get out of the house to work.

#

And despite this virtuous cycle, you know, women's participation in the labor force is going down.

#

And I meant to ask you a question earlier. Well, we were talking about that, but I forgot.

#

So I'll ask that and then we'll go back to Haryana, which is about, you know, Claudia Golden.

#

You must be familiar with her work, wrote about this famous U shaped curve where, you know, as countries grow more advanced in the technology scale, less women work.

#

But then that changes as again more women work.

#

Does that curve apply to us? Are we at the low end of that curve or is something else happening entirely?

#

So I don't have a crystal ball and I don't think anybody does.

#

So we were definitely at the downward trend of the U curve and we're going on sliding.

#

You know, as you mentioned, demonetization, everybody made such a noise, you know, the headlines in every paper about job loss.

#

Nobody pointed out the fact that the job loss was entirely amongst women.

#

Zero point nine men actually came into jobs after the first four months of demonetization.

#

It was the women who lost jobs.

#

So somehow again, it's a silent crisis that we don't see and it is going on sliding down from twenty seven down to twenty five percent.

#

We don't know where the slide will end and when we'll bounce back.

#

There is no way of telling when that will happen.

#

We do have a jobs crisis and I would like to just mention over here that it's almost as if jobs have become the new banana.

#

What do I mean by that?

#

I mean that in the old days, you often heard these stories about if a family is very poor and they had one banana, they would give it to the son.

#

Right. Not to the daughters.

#

So jobs are that new banana.

#

So within families and I will not take the name of a minister from my favorite state of Haryana. It's not my favorite state.

#

Is this a state I've traveled to a lot?

#

It's totally your favorite state.

#

We're on the record now.

#

The gender record is awful, appalling, really appalling.

#

And this minister told me, he says, why are you doing so much women's labor force participation?

#

So you must understand politically.

#

Why is it that political parties, you know, they don't when political parties talk about women's empowerment, what are they talking about?

#

CCTV footage, you know, crime rate.

#

That's all they talk about.

#

Nobody talks about jobs for women.

#

And the reason why they don't talk about it is because they realize that, you know, when a man loses his job, he will come out on the street and agitate.

#

Let's imagine 19.6 million men lost jobs in just a decade.

#

Would there be such silence in the media amongst social groups amongst feminist groups amongst?

#

I mean, in every sector, there is nothing that is silence because where are those 19 point?

#

I'll tell you one of the most difficult things that I faced while doing the series is finding women who had quit jobs because when a woman quits her job,

#

she just melts into her kitchen.

#

You cannot find these 19 point six million women.

#

They're not in Jantar Mantar protesting.

#

The men would have brought the government's down successive governments down of 19 point six million men.

#

It would have been a massive crisis on the front page of every newspaper and on the top of talk shows and on every TV channels.

#

And that's a very evocative and moving phrase melts into her kitchen.

#

You know, I remember this column last year by a columnist I won't name here, but it kind of made me very angry where the column basically made the argument

#

that it's fine if women don't work and they do the unpaid work they do at home because that is more optimal for society, which really pissed me off.

#

And I was editing Prakriti at that time.

#

I got one of my colleagues, Devika K to write a piece about that because sort of rebutting that.

#

And that seems to me to be an analogue of the kind of argument you once heard and still here sometimes in the context of caste,

#

where even Gandhi made the argument once that there is a purpose for the caste system and is good for society,

#

that it's like that and everyone has the roles that they must play.

#

And how does one respond to arguments like this?

#

Oh, that is such bullshit.

#

You know, this whole business of how when women actually you have men, male economists and economists,

#

I mean, saying basically, oh, women dropping out of the workforce is actually a good thing because this means that A,

#

the economy is progressing.

#

So the U curve syndrome that you spoke about and B, this is pitched as a wonderful luxury for women.

#

Why do you want to work?

#

Why do you want to rush in the metro for a job?

#

You can sit at home, relax and make food twice a day because your husband doesn't want to eat.

#

So it is pitched as a luxury, as something that is aspirational and as a step forward for women.

#

You know, motherhood is endowed with such a lot of sublime and everywhere in the popular culture.

#

If you look at ads, you work with an ad agency.

#

For eight months, 25 years ago, don't hold it against me.

#

And you have these, you know, butterflies and mother's love and mother's care and, you know, it's like this noble.

#

You know, my God, being a mother is the greatest thing any woman can do.

#

I mean, why is not fatherhood endowed with that same some of that same nobility?

#

So a woman who says, well, I would rather have a career than sit at home and look after my children, you know, is a very, very bad woman.

#

She's the woman we fear the most.

#

We do not approve of that woman who says, I'd rather go to work than sit at home looking after my babies.

#

And something else I want to talk about is family values.

#

So, you know, I was chatting today with a friend of mine and he said that one of the great problems in America today,

#

one of the great social problems is a breakdown of family values.

#

And there's no phrase I hate more than that.

#

I mean, I just thought that the very problem with India is bloody family values.

#

I do. I do agree. Unpopular as this may make both of us.

#

The family look families, as we said, there are families and families.

#

Jyoti Singh Pandey's father is my role model, you know, a man who can sell his.

#

But how many fathers are there like like that?

#

It is so when we talk with when I say that what is holding women back, why are women falling off the workforce?

#

The good news, the good reason why some of them are falling off the workforce is because they're in education

#

rather than in employment. Fine. That's the good news.

#

But what is the other reason? And the main other reason, you know, when you say patriarchy, patriarchy sounds like this wonderful,

#

long word that masks a very ugly reality of Indian families because it is families that impose stereotypical roles,

#

stereotyping on sons and daughters. This is a girl's job.

#

This is a boy's job. When a girl wants to go out to work,

#

she must take the permission of her father, her brother, her father-in-law, her husband,

#

and sometimes even the entire village panchayat.

#

So I'll give you an example. The hospitality trade. There is a huge demand for skilled women.

#

You know, the hostage. But it is the family that says array.

#

But this is not good work for our daughters.

#

And I have spoken to fathers who have said my daughter is not going to serve food to men in a restaurant.

#

You know, you make her a captain. How can she become a captain unless she's first serving?

#

So there is a demand. The jobs are there.

#

But the families say this is not appropriate or the village will say this girl.

#

So there's an institute that's training women for the hospitality trade in Aurangabad.

#

This is run by Pratham. And the women all who enroll, who get in,

#

they actually get their fees are subsidized to a very, very large degree compared to men.

#

Yet, despite the subsidy, only 30 percent of its intake is women.

#

And of those 30 percent, a large proportion who get job offers after they complete

#

don't accept their jobs because the girls are coming from tribal belts, from far away villages.

#

And the families, first of all, don't want to send them even to train.

#

And second of all, when they send them to train, don't want them to live that far away.

#

So they are allowed to come in batches. If they come with three, four, five from the same village, they send them.

#

But then three, four, five cannot get a job in the same place.

#

They have to be separated. And once girls are separated, the parents don't want to send them off.

#

And I'll never forget this one man I met. He was so angry.

#

He was a truck driver and his daughter had done the course and she had actually joined it while he was off

#

traveling somewhere, were driving his truck.

#

And when he came back, he discovered that she had joined this hospitality course.

#

And he was very angry because he had not been consulted.

#

And he just went on and I said, but what's wrong? She had a job offer.

#

So he's he's the one who told me, oh, captain, go job to you.

#